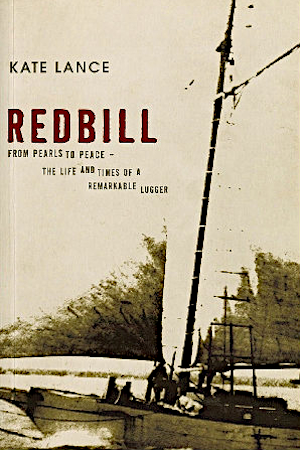

Extract from Redbill: From Pearls to Peace

Copyright 2004 Kate LancePublished by Fremantle Press

ISBN 9781920731427

Summary

Redbill is the true story of a sailing boat's voyage through a century of Australian history. She began life as a lugger owned by the buccaneering pearling master Captain Gregory, then as naval vessel HMAS Redbill, she was bombed in the Pacific War by the Japanese.

In the 1990s she worked for Greenpeace, raised funds for East Timor refugees, and reunited a young Aboriginal man with his family. Finally, Redbill took on an epic voyage around Australia, to return to the North-West and face her greatest challenge yet: Rosita, the most powerful tropical cyclone to strike Broome in ninety years.

Introduction

This is the story of a large wooden boat named Redbill that began life as a pearlshell-diving lugger in the early years of twentieth century Australia.

Redbill was once owned by the notorious Captain Gregory, a master pearler who was not only the inspiration for the dashing hero in a handful of novels, but the subject of bitter rumours of betrayal; a man famous for his buccaneering ways and his friendships with Asian people in the days of strict racial segregation. For two decades he calmly deceived governments with his Japanese-crafted pearling fleet of illicit phantoms that, one-by-one, took over the identities of his officially registered vessels, and Redbill was to become one of those phantoms.

Redbill ’s long life as a lugger was unusual enough: she worked out of most of the north-west ports and in Papua, during four very different pearling eras that spanned sixty years of the industry. Yet what was even more unusual was that she went on to a whole new life when traditional pearling came to an end, while the others of her kind were left to rot on the foreshore.

Over the years Redbill was rebuilt and repaired many times. She was threatened in wartime, abandoned as worthless, sunken, negelected and often forgotten, yet somehow she always survived; perhaps because she had an almost uncanny ability to inspire the kind of love and hard labour it took to return her to seaworthiness.

In wartime Darwin Redbill was commissioned into the Royal Australian Navy as one of His Majesty’s men-of-war. In Papua she went crocodile-shooting and pearling with one of the few ‘white divers’ of the time, then lived with a tribe of ex-headhunters as they revived their traditional arts after decades of discouragement.

Redbill went to work on behalf of Greenpeace, with ecological surveys in the Barrier Reef, environmental protests around Australia and a voyage all the way from Tasmania to Tahiti and back to defy the French in the South Pacific. She raised funds for refugees from East Timor, filmed a TV documentary on troubled teenagers sailing through the wild islands of Bass Strait, and helped reunite a young Aboriginal man with his long-lost family.

Redbill took on an epic voyage around the coast of Australia to return to Broome, where in 2000 she encountered her greatest challenge yet. Over decades she had survived dozens of terrifying storms, but this time, alone, she had to face Rosita, the most powerful tropical cyclone to strike Broome in ninety years.

Woven throughout Redbill’s story is the thread of simple happiness felt by everyone who knew her. Witness to a century of Australian history, there was (perhaps) no magic to it; Redbill was just a boat – a large, lucky wooden boat – but she was one that set sail with extraordinary people.

1. Shell Games

. . . the continual coming and going of the pearling boats giving an air of activity, whilst the trade they create makes for the general prosperity . . .

- J. S. Battye, The History of the North West of Australia, 1915

Every year, born in the warm island waters of Indonesia, tropical cyclones sweep around to make landfall on the north-west coast of Australia: a wilderness of river gorges, bushland and desert, renowned for its exquisite light and colour. Famous, too, as the pearling coast, with its heart at Broome, a small port of turquoise water, red mud and green mangroves. Broome was once the origin of the finest mother-of-pearl shell on the planet, and its fortunes were founded on the luggers, large wooden boats with rectangular sails: the sturdy, smelly, unglamorous workhorses of the pearling fleet. One of them, built at Fremantle in 1903, was a lugger named Redbill.

In the early years of the twentieth century Redbill was just one of almost seven hundred of the hand-crafted sailing boats fishing for pearlshell in tropical waters from Western Australia to the Torres Strait. Like a flock of angular white creatures jostling at the water’s edge, the luggers were once as common, and as disregarded, as seagulls.

The Broome lugger fleet before World War I. The 1904 lugger Redbill had a straight stem like the boat on the far right.

Redbill had a twin – Ibis – named, like Redbill, for a water bird. They were built side-by-side in Fremantle by shipwrights Chamberlain and Cooper, launched in 1904, and worked together for over forty years. At that time they were gaff-sailed schooners, that is, they had rectangular sails on two masts, the taller mast at the rear. They were about 36 feet in length and 12 tons registered tonnage (a measure of volume, not weight). The term ‘lugger’ came from the older lugsail-rigged fishing boats, but was widely used for pearling vessels, even though most were really ketches or schooners. (Ketches have the shorter of the two masts at the rear and within a few years became the preferred rigging style for luggers.)

Redbill was nearly 12 feet wide and had a shallow draught, just over 6 feet from the deck to the bottom of the keel. She had a long counter stern and her stem was straight or ‘plumb’, a distinctive vertical profile from bowsprit to waterline. Like the other luggers Redbill was especially strengthened to handle the strain of frequent beaching from the enormous tides of the north-west: falling and rising up to nine metres in height.

‘Redbill’ is the name for the rare sooty oystercatcher (Haematopus fuliginosus or H. opthalmicus), a large, shy black bird which lives only on the rocky coastline of Australia. Oystercatchers have an endearingly solemn manner. An artist who has observed them over many years said: ‘They seem cautious, not fearful; they peer at you with their beautiful eyes and look practical, utilitarian, somehow thoughtful. They’re immediately appealing; they have a powerful presence that other birds don’t seem to have.’

Redbills have scarlet eyes, black feathers and long red beaks as straight as bowsprits, with which they prise open small molluscs. It would be hard to find a more suitable name for a pearling lugger than that of the shell-fishing, ocean-loving sooty oystercatcher.

A Redbill, Haematopus fuliginosus.

* * *

In 1688, fully a century before the landing of the First Fleet, the ‘Respectable Buccaneer’ William Dampier had noted rich beds of pearl oysters as he travelled the shores of Western Australia. From the 1860s onwards there were small ventures along the mid-west coast gathering shell from dredging, beachcombing and shallow diving, but they came and went with minor success. Further north, a broad sheltered inlet named Roebuck Bay was found to be full of pearlshell, and there the port of Broome was gazetted in 1883, nearly two hundred years after Dampier. Then it was no more than a few rough foreshore camps, but within two decades it was to become the wealthiest pearling town in the world, the ‘Queen City of the North’.

Broome was constructed out of the life-and-death labours of Japanese, Malays, Timorese, Filipinos, Chinese, Aborigines and Europeans, and today celebrates a mix of racial heritages that is unique in the country. At a time when the rest of Australia was frantically excluding most of the world from its shores under the infamous White Australia Policy, Broome cheerfully accepted anyone who could cope with the appalling conditions of the pearling industry, threw them together in a small red-dust town, turned on heat, peril and cyclones, and brewed, for a time, an extraordinary culture.

Out of the north-west streamed shell the size of soup plates, to ornament the palaces and churches of Europe and to adorn fashion, furniture, jewellery, watches and instruments; at one time Broome alone supplied sixty percent of the world’s mother-of-pearl. The shell was the species Pinctada maxima, which could grow to 25 cm, 10 inches, in diameter and had two varieties – gold-lip and silver-lip, named for the flush of pigment around the inside edge of the shell. (In modern pearl farming, silver-lip shells produce white, lilac and silvery pearls, while those from gold-lip are tinted cream, rose and champagne.)

For thousands of years Aboriginal people had collected pearlshell for their own trading across Australia. It was seen as the essence of water – life itself to desert people – and was engraved and worn as ritual and decorative ornament. When the Europeans arrived, they offered Aboriginal people trade goods in exchange for shell collected by diving in shallow water. They were sometimes shockingly abused by unscrupulous pearlers and in 1871 laws were passed to prevent indigenous women and children working as divers. Cheap labour was essential to the industry, so Malays, Koepangers (Timorese), Chinese, Manilamen and Japanese were brought into the country to replace them.

In the late 1800s new protective suits with metal helmets and a constant supply of air permitted shellfishers to go to as deep as twenty fathoms – nearly forty metres. The new equipment was called the diving-dress or simply, the dress (the term ‘hard-hat’ was 1950s American slang, not used by traditional divers in Australia). Air was pumped by hand, using great wheels to compress it down the air-pipe to the diver, and the humble wooden luggers were what made it possible to take men and equipment far out to sea and bring home tons of valuable pearlshell.

Around 1900, prices for shell rose dramatically and a maritime gold rush began. Registrations in Fremantle for pearling boats, usually ten or so a year, reached a peak of 103 new vessels in 1903, and Redbill was an offspring of this frenzy of creation.

* * *

Redbill ’s official number as a merchant vessel in the Register of British Ships for the Port of Fremantle was 119011 and Ibis’s was 119018. Both luggers had been commissioned by a partnership of pearlers: Frederick Parkes, Herbert Parkes and Arthur Harding. When Redbill and Ibis were launched in February 1904, Fred Parkes noted in his ledger the cost of four shillings to register them and five shilling on drinks for the shipwright. Two years later the partnership with Harding was dissolved and the Parkes brothers became sole owners. By then they both carefully specified their occupation in the Register as ‘Gentleman’ rather than the somewhat more disreputable ‘Pearler’.

Their company, F. L. Parkes and Co., had been founded in 1897 by ex-sea captain Frederick Lee Parkes, semi-retired in Perth and now interested mostly in bowls, Freemasonry and his large property portfolio, and younger brother Herbert Maurice – Bert to his family, but known to his friends as Daisy. It was Bert who actually ran the business from Onslow, a tiny port near the westernmost point of the state, roughly half-way between Perth and Broome.

Onslow had been settled at the swampy mouth of the Ashburton River as a landing for supplies to pastoralists and pearlers in the mid-1880s. Its history was shaped by two factors: jetties and storms. The region has the distinction of being perhaps the most cyclone-prone place on Earth, and the first two town jetties on the river fell to the weather. A new jetty on the nearly coast was built at the turn of the century, but it was not long enough and quickly silted up. During Redbill’s years as an Onslow lugger the town was dominated by the question of what to do about a deep-water jetty and indeed, what to do about ramshackle, uneconomic Onslow itself.

The Ashburton River was a poor anchorage, prone to tidal surges and floods, so luggers were often based in a cluster of little islands, the Montebellos, located about 150 km north of Onslow. They are low, weathered limestone hillocks, with scrubby vegetation, little fresh water, wild sandy beaches and clear seas teeming with life. There are roughly one hundred islands in the group, the largest of them Hermite, Trimouille and Alpha. Pearlshell from the Montebellos grew to enormous sizes, and the islands were the site of an early attempt to culture shell by Thomas Haynes, who took out leases in 1902. His experiments were frustrated by infestations of ‘bastard shell’, Pinctada albina, identical to pearlshell when tiny, but reaching only a few inches in size.

The Parkes set up a foreshore camp and a shed at Lugger Cove, off Stevenson’s Channel on Hermite Island, but despite their best efforts they seemed fairly unlucky where their small fleet was concerned: lugger Rescue was wrecked at Baldwin Creek in 1897, Willie at Cygnet Bay in 1900, Sea Gull was lost off the North-West Cape in 1900, and after they sold Taniwah she was taken by a mutineer crew and sunk in 1908 at Gantheaume Point near Broome (although the Parkes can hardly be blamed for that).

The company insignia was a white five-pointed star painted on the bows of the luggers. Next to the star was the pearling licence number, required by law, and Redbill’s number was O5 and Ibis’s O6 –‘O’, of course, for Onslow.

Parkes and Co. luggers in the Montebello Islands in 1913. Redbill's sister ship Ibis, O6, is at the left, showing the star insignia of the company. Note the men in dinghies at the stern. The lugger on the right may be Redbill.

Although boats were licenced to specific ports, they would fish for pearlshell anywhere that seemed promising along the coast from Exmouth Gulf to King Sound. They were traded, sold, leased and loaned between pearlers, and the conditions for luggers and their crews were much the same throughout the whole region. The Western Australian ports reach their all-time high of pearling vessels in 1907: that year Onslow worked 29 boats and Cossack 27, while Broome dominated the industry with 357 luggers.

It was a hard life, but must have seemed worth it: pearlshell sold for £150 to £250 per ton and a good boat could bring in five tons in a year. Pearls themselves were a bonus – perhaps one every few thousand shells, with only one in a hundred of those a true gemstone. They offered the element of luck that inspired the gamblers of the industry, but the backbone of the trade was the iridescent mother-of-pearl. Diving took place from fleets of luggers which would stay at sea for weeks or months at a time, provisioned by large schooners. The mother ship from each company would collect the shells, which were opened under the supervision of the white master or shell-opener, watching for any easily-misappropriated pearls.

Parkes and Co.’s mother ship was a pretty schooner named Cutty Sark after the famous tea clipper preserved today at Greenwich; the Parkes’ Cutty Sark, however, was not quite so fortunate. Her finest hour came when her flags decorated the Church Hall at Onslow (due to lack of local greenery) when the Governor visited in 1906. However, in March 1907 a cyclone struck Exmouth Gulf and five Japanese men were drowned; fifteen luggers, Redbill and Ibis probably among them, were driven ashore; and Cutty Sark, ‘on her beam ends with her port side stove in’, was completely wrecked.

* * *

Out on the luggers the rhythm of the seasons defined the lives of the boats and men as if they would never end. The year for Redbill began in February or March, close to the end of the monsoon season – not close enough many felt, as a number of cyclones still occurred into April – but economic reality demanded that the boats return to work.

Luggers in this period usually carried a crew of seven. The master or shell-opener and the first diver shared a tiny cabin at the rear of the boat, while the rest of the crew slept in two-tiered bunks in the forepart. There were large tanks of fresh water amidships and to starboard of the tanks was an open hold for the hand air-pump and a small fireplace, for cooking with the red mangrove wood that burned away to almost nothing.

The pearling life was sometimes achingly hard. Luggers went to sea for weeks or months at a time, food was monotonous, work lasted from dawn till dark and crew members could be lethally hostile towards each other. The boats stank of rotting shellfish and crawled with giant cockroaches that would nibble the skin off pearlers’ toes as they slept.

Yet the scenery of the north-west is startlingly beautiful. Photographs from the old days, with their soft sepias and greys, cannot do justice to a landscape that glows like gemstones – soils of garnet and amber, waters of jade and aquamarine. Despite the demands of their work, pearlers must have taken at least some sense of pleasure from their surroundings. Autumn and winter days were unclouded and brilliant, and night offered stars, moonlight and soft breezes. Divers had good pay, high status and great pride in their abilities; and although it was a dangerous life, it clearly appealed to many.

The lay-up season was summer, and during a rising spring tide in December the luggers would return to the foreshore camps of their home ports. All equipment would be stripped, carefully labelled and stored. Crews would dig channels into the mud and the luggers would spend months cradled there by pillars of sandbags, washed by the tides. While equipment was repaired or replaced, tons of pearlshell would be carefully graded and layered like china in crates in the packing sheds.

Summer was intensely hot and humid, with almost daily thunderstorms and the ever-present threat of cyclones. Outside of their labours the lugger crews spent the time drinking, gambling, and cramming as much human pleasure into their lives as possible in a few short months, until it was time to ready the boats to go out again for the next pearling season.

* * *

On the desk in front of me is an aquarium ornament, a deep-sea diver with a treasure-chest. I remember childhood cartoons – sunken galleons, cheerful whales, giant clams, Tom (or Jerry) wide-eyed or cunning in a bubbling helmet, with a dancing octopus, a sunken sailing-ship, a swordfish cutting through the air-line … what fun! From hard labour, to cartoon cliche, to a cheap toy for the goldfish bowl, the now unimaginable lives of pearlshell divers have passed through and out of our collective memory. Yet it was all too true: air-hoses snapped, ships sank and divers died in a variety of ugly and painful ways. It was no cartoon.

Around 1910 engine-pump air compressors started appearing which could increase working depths to 35 fathoms (65 metres). This led to a massive leap in deaths from ‘diver’s paralysis’ – the bends. Unless divers returned to the surface in gradual stages they risked agonising paralysis or death, but often carelessness or emergencies brought them to the surface too quickly. In the years from 1910 to 1917 one hundred and forty-five Broome divers (from a fleet of 300 or so boats) died horribly of the bends. There were other risks too, of course: tropical waters hosted a wealth of sea creatures that like to eat, poison, sting, grasp, or simply entangle with those humans who found themselves at the business end of thirty fathoms of air-hose and life-line.

The diving dress itself was a epic of preparation. The diver would don two suits of flannel pyjamas, heavy woollen trousers, sweater, quilted breastplates, thigh-length stockings and moleskin underboots, then wind four yards of flannel around his middle. He would climb into the neck of the rubberised canvas diving-dress and his tender would fit a steel corselet, curving down over chest and back, to the neck of the dress with winged nuts. He would be helped into his lead-soled, brass-toed, leather diving boots, then climb over the side of the boat, where, half-submerged, an extra fourteen pounds of lead ballast would be attached to his chest and fourteen more to his back; then the metal helmet would be clicked onto to the corselet with latches like a pressure-cooker. The weight of man and dress was estimated at close to four hundredweight – about 200 kilograms.

Luggers usually drifted with the tide, their divers forced to move constantly forward looking for pearlshell in the small space in front of them – they could not go backwards or too far sideways. If the air-hose or line became looped around an obstruction and the diver could not signal his tender to halt the boat in time, then his links to the surface would snap and he would probably die.

Strangely, as the diving-dress gradually disappeared in the 1960s, another, similar image arose to displace it: the clumsy moon-dress of the astronauts, based on the same principle – keep inside what is needed for life, keep outside what will kill; but sadly the diving dress was not quite as good at its job as the astronauts’ suit.

* * *

After the loss of the mother ship Cutty Sark in the 1907 cyclone, Parkes and Co. bought an elderly schooner named Rescue and a new lugger, called Hawk after an old one also sunk in that storm. The years 1908 and 1909 brought record catches around the Montebellos; Haynes’ culture experiments were given the credit, but since his shell failed to grow everywhere else there was probably little connection.

The new Parkes boats were soon put to the test; in January 1909 a cyclone battered Onslow that lasted for forty hours. Rescue and another lugger lost their masts, while seven of Parkes’ other boats sheltered at the Bay of Rest, where the surging water rose twenty feet above the high tide mark. Four of them lost their masts and another was beached.

However that was not the end of it for 1909; in early April a fierce storm struck Onslow. Six inches of rain fell, and a number of vessels sheltered in the Ashburton River were driven ashore. The Broome Chronicle of 10 April reported: ‘Anxiety is felt for eight other luggers which put out to sea on Monday, no tidings of which are to hand. No boats are available to go out and search.’ On 17 April the Broome Chronicle ‘confirmed a sad tale of loss of life and property’:

[Parkes’] luggers Penguin, Seagull, Elsie and May lost, and 24 Malays with them. One Jap lost off lugger Ada which had a terrible experience in the vortex of a willy willy . . . Search parties, Messrs Parkes and Locke, out looking for wreckage . . . but all hope of saving life has been abandoned.

Twenty-five men from the luggers drowned at sea, around one-fifth of all of the indentured crewmen of the port of Onslow and half of the Parkes’ workforce; it must have been a devastating time for the Asians who survived, but this is the only mention of the deaths in the newspapers.

Redbill and Ibis rode out the storm among the other Parkes boats, of which ‘three dismasted, one half-mile inland; only one remaining complete’.

* * *

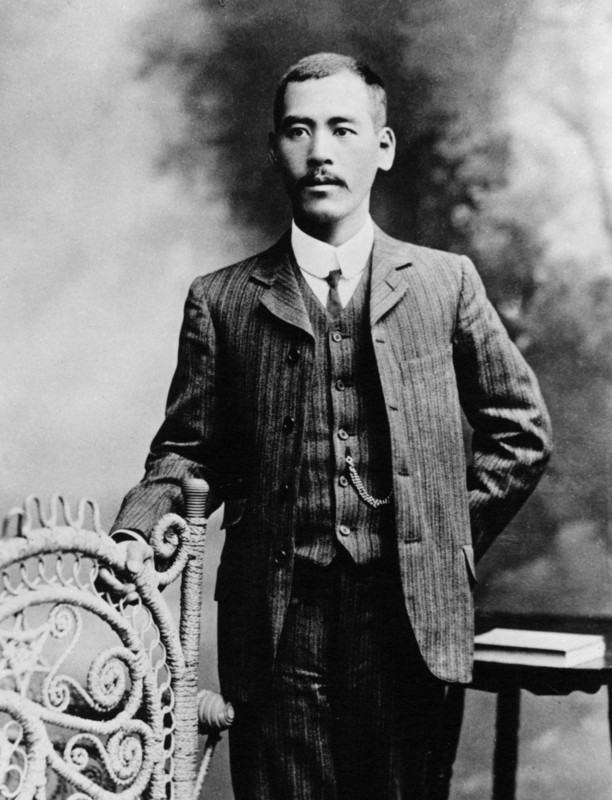

While the Parkes and Co. luggers were pearling the turbulent waters of Onslow, an extraordinary person was rising to prominence in Broome; a Welsh sailor named Ancell Clement Gregory, who would one day become master of Redbill and take not only the luggers but the pearling industry itself in a whole new direction. Unlike the Parkes, Captain Gregory always regarded his occupation as ‘Pearler’ – and few would ever have termed him ‘Gentleman’.

Captain Gregory had trained on the great square-rigged sailing ships of the turn of the century. Born on 1 July 1878 at Bishopston, South Wales, he had gone to sea at sixteen and over the following eleven years he worked on windjammers carrying cargo between ports all over the world. His references were excellent (‘strictly sober, clever, exemplary’, ‘gave every satisfaction’, ‘recommend him with every confidence’), and by January 1906 he had become Chief Officer on the steam-ship SS Charon, trading between Singapore and Fremantle and stopping at Broome. He left the ship after six months to ‘take charge of a Pearling Business in Broome … thoroughly capable and energetic Officer … we regret to lose his services’.

At the age of twenty-seven, Gregory – clever, ambitious and restless – had recognised an opportunity in the red dust and turquoise waters of tiny Broome: he became manager of C. N. Murphy’s twenty-eight luggers – then the largest fleet in Western Australia – when Redbill was only two years old and working eight hundred kilometres away to the south-west.

No-one dared address Ancell Clement Gregory by his Christian name. He was known only as Greg, Captain Gregory, or the Skipper (Master in Sail Certificate No. 035062) – a passionate, intelligent, striking man, who aroused great emotion in those who knew him. Mary Albertus Bain quotes ‘a business-man from overseas’, who said that in forty years he had never met so brilliant a person as Gregory. He was over six feet tall, ‘handsome and daring, with a touch of a polished showman in his makeup, but capable too, of violent outbursts of temper …’

Hugh Edwards describes him as dark and dashing, renowned for his immaculate tropical whites tailored in Singapore and his cigarettes rolled personally for him in Cairo. He was athletic enough to famously test his sobriety by kicking the ceiling fan in the bar of the Continental hotel when aged in his mid-forties, reported Tom Ronan, a young shell-opener. Ronan made no secret of his dislike for just about everyone, particularly women, modern writers, Aborigines and Japanese, but oh, how he worshipped Captain Gregory:

White-suited and white-helmeted he was, with the torso of an athlete, the light legs of a seaman, and the face of a satyr: a devilishly handsome satyr, but as pagan, as restless and as ruthless as any that ever roamed the hills of old Attica.

Captain Ancell Clement Gregory, master pearler, about 1910.

Yet for all of the admiration that Gregory attracted in his busy career, he was as often vilified. Sometimes it was envy of his good fortune – itself the result of his infuriating charm and energy – but more usually it was because of what was perhaps the most extraordinary aspect of Ancell Clement Gregory: that from his first meeting with a Japanese photographer named Yasukichi Murakami, the two men formed a loyal friendship that lasted for all of their lives.

This was a time when ‘Asiatics’ were regarded, with the full force of the law, as less than human; when a white man associating by choice with non-whites was a traitor to his race – at best, dismissed in disgust as ‘unsound’. From the Asian side, bias was just as uncompromising; Europeans were no more than naive bullies, lacking any sense of honour or civilization.

Yet in remote little Broome, Welsh Gregory and Japanese Murakami discovered in each other like-minded souls – witty, ambitious and perceptive – and both endured the disapproval of their own kind for decades in exchange for the rewards of their friendship.

Mr Yasukichi Murakami, trader, photographer and inventor, Gregory's business colleague and friend for thirty-four years.

* * *

‘Cockeye-bob’ was the local name for a brief, intense squall that would strike suddenly, with ‘titanic white and black fleeces rolling one on top of the other’. A more powerful, longer-lasting storm was a ‘willy-willy’ and the fiercest of those were hurricanes or cyclones. Luggers were most vulnerable to the weather off the great sandy sweep south of Broome, then called the Ninety-Mile Beach, now known, oddly, as the Eighty-Mile Beach (even more oddly, it must be at least 120 miles long). It offered just a few points of shelter, shallow creeks that could be entered only at high tide. Any boat caught out in a willy-willy on the rich pearling beds of the Ninety-Mile was in great peril.

In late April 1908 an unexpected storm struck La Grange at the northern end of the Ninety-Mile: ‘As it was known that the pearling fleets, under the impression the cyclonic season was over, had gone out, grave fears were entertained for their safety’, reported the Northern Times on 2 May 1908. Those grave fears were well-founded; three schooners, forty luggers and one hundred and twenty-three men were lost. (The three white men among them were mourned in the papers; the one hundred and twenty Asian men who also died were never even named.)

Later in December that year a group of boats were anchored near the Ninety-Mile, salvaging wrecks from the April storm. They included the 150-ton Kelander Bux, the beautiful mother schooner skippered by Captain Gregory, which was famous for her skillful crew in their dashing uniform of sarongs and red caps.

A cyclone closed in on the fleet at night on 7 December. Next morning the luggers made a run for Cape Bossut Creek, but the much larger Bux, despite a desperate effort to escape, was caught and smashed up in the massive surf. Most of the crew managed to get to the dinghies or cling to wreckage; Gregory swam ‘with half a door’ and got to the beach after many hours. He made his way north along the desolate Ninety-Mile and met three of the crew. They found fresh water in a stranded lugger after walking all night, met another three of the crew the following day, then finally reached the stranded schooner Alto. Gregory was interviewed by the Broome Chronicle of 26 December 1908:

On arrival at the Alto we were treated by the staff with every possible kindness . . . The crew – South Sea Islanders and Malay – behaved splendidly from first to last. No vessel could stand the fierceness of the gale after she struck, with mountainous seas 40ft high. The Bux was a fine able schooner, and given plenty of room would weather anything . . . [but it was] impossible to run across the front of the cyclone owing to the closeness of the lee shore . . .Three of the ten men on board the Bux died. The survivors had lost everything they owned, but the bosun told the Broome Chronicle that Captain Gregory had given all of them clothing after they returned to Broome. Over forty men, two schooners and fifteen luggers were lost in this storm.

Gregory’s sober and generous account contrasts strikingly with that reported in the colourful fantasy Forty Fathoms Deep, which had Gregory floating in the water for two days, being one of only two survivors, and staggering up the beach for another three days with a dead gannet in his hand! (Almost all published accounts of the Kelander Bux story contain wild exaggerations – it must have been a classic pub yarn.)

It was probably at this time too that 30-year-old Gregory and 28-year-old Yasukichi Murakami first met. Murakami was born on 19 December 1880 in Tanami, Wakayama Prefecture, Japan and arrived in Broome in 1901. Bain described him as ‘a strong, youthful person with an outgoing, bright personality’, who became highly influential in his own community and mixed easily with all levels of Broome society. He was not only a businessman, but a professional photographer at a time when it was a highly specialised technical discipline, and in later years was also a visionary inventor. His son Joseph wrote that his sister Yasuko Pearl Minami had told him of their father’s first meeting with Captain Gregory:

. . . a dishevelled, unkempt stranger came into our father’s premises and asked our father, a relatively prosperous man at the time, to lend him some money. Normally no-one would take much notice of such a wretched-looking man but Yasukichi, with considerable misgivings, decided to lend him about twenty pounds, a large sum at the time, believing that he would never see the man or the money again.Some years later, recalling the event, Joseph asked Yasuko why Gregory had been in such a ‘wretched’ state that day:

Yasuko immediately replied that our father had told her that Gregory had been in a shipwreck and had swum all the way to shore and safety. He looked so miserable that Yasukichi felt sorry for him and decided to lend him the money regardless of the prospects of being repaid.The shipwreck could only have been that of the Bux, and Yasuko’s words explain a great deal. Gregory had been established in Broome for two years by this time so he probably had no need of the money himself; it seems plausible that it was to provide for the destitute seamen – those South Sea Islanders and Malays who had ‘behaved splendidly from first to last’. So in December 1908 it was probably Gregory’s care for his crew and Murakami’s generosity to a stranger that led to the partnership that would repay both men many times over through the coming years.

Murakami helped finance Gregory’s first small fleet, while Gregory assisted him in return during his own difficult times. The importance of their bond is indicated by the fact that while Gregory was overseas in Britain in 1912, he scandalised the town by allowing Murakami to live in his home, a gesture that calmly flouted every racial barrier of Broome society: he was powerful enough then to get away with it.

Gregory’s younger brother, Fleming Clement Gregory, nicknamed Dick, had spent ten years with the British Army in India. When he visited Broome in April 1908 he ran into a cyclone the first time he sailed out on the luggers, but he still decided to stay and set up a business with his brother. In 1909, discreetly assisted by Yasukichi Murakami, they bought four luggers – Postboy, Struggler, Fanny and Idalia – for the new enterprise of Gregory and Co.

Also in 1909, to the fury of the other pearlers, Captain Gregory landed the job of Harbour Master, Marine Surveyor and Inspector of Shipping at Broome. They thought that he might profit as a pearler by knowing their sailing plans and they may have been right, but Gregory carried out his duties carefully and conscientiously; he was one of the few professionally-trained officers among the many ‘one-boat admirals’ of Broome. As Harbour Master, Gregory piloted the first Australian warships, HMAS Yarra and HMAS Parramatta, on their initial voyages in Australian waters, and when in Britain in 1912 he supervised the fitting out and dispatch of two steamships for the State of Western Australia.>To at least pretend to avoid a conflict of interest, Dick was the registered owner of the Gregory and Co. vessels, but the Skipper was clearly the one in command.

In an era when the work safety of even white labourers was of little concern to employers, he prosecuted Captain Fred Everett in 1911 for not providing lifebelts on a lugger which had sunk, drowning two Asian men. The case was lost because, amazingly, luggers were classed as fishing vessels so they were not required to carry lifesaving equipment, yet it offers an intriguing insight into Gregory’s attitudes towards the pearling crews compared to those of the other masters; perhaps more thoughtful too, because he had himself experienced the terror of shipwreck.

* * *

It was a golden era for the north-west. The pearling industry had its problems but no-one was paying much attention – they were having too good a time. Broome had gambling houses, billiard halls, brothels, Asian eating-houses, market gardens, opium dens, sumo wrestling, tennis courts, newspapers, Japanese hot baths, Chinese laundries, six pubs, a soya sauce factory, a race course, a circus and two outdoor ‘picturedromes’.

During those years it was a small country town slowly gaining in confidence, rather enjoying its unusual role on the wild north-west frontier. Newspaper articles from the south about the ‘exotic’ life of Broome were reported with amusement, yet in the local paper earnest articles on hurricanes, pearls and diving decompression sat comfortably beside those on chicken-raising, dressmaking and household hints. The West Australian Pearlers’ Association was flourishing, a telephone system had been installed, and electric power was on the way.

Cars, too, came to Broome and among the first to have them was (of course) Captain Gregory. Yasukichi Murakami also bought a car in 1912 and employed a white man to drive it as a taxi for Asians, a wonderful novelty. His driver, Hubert Hanstead, was fined £5 for overcrowding and speeding: the limit was twelve miles per hour (six around corners).

Broome had an annual Yacht Club regatta for working luggers – crewmen could attend for free – and busy Turf, Rifle and Cricket Clubs; there were servants and formal balls, with the womens’ lace and silk gowns listed like rainbows in the newspaper. The colonial life played out against a backdrop of dusty red earth, jade seas, gold frangipani, scarlet poinciana, green palmtrees, and towering black storms.

Asian society was as stratified as the European. At the top were the long-term residents – the Japanese doctor (consulted even by the white women), the wealthier businessmen and the pearl-cleaners, whose skill could add hundreds of pounds to the worth of a pearl. Further down were the head divers and the shop, brothel and gambling-house owners who lived in the iron and wood buildings of ‘Japtown’, and at the bottom were the indentured crewmen living in the foreshore camps.

The Asians had national clubs which held feast days and ceremonies; the Japanese would celebrate the Mikado’s birthday with flowers, and hold sombre, beautiful O-Bon Matsuri in August, with small lantern-lit luggers sent out to sea at night to commemorate the dead. Malays, Chinese and Filipinos would hold processions, fireworks, regattas, new year celebrations and colourful religious meetings.

The Aboriginal people were the most marginalised of all, in humpies and shacks on the outside of the township, although many still had strong links to their traditional way of life. Disease, neglect and alcohol took their toll, but unlike other parts of the country there was little open conflict between the Broome Aborigines and the pearlers, who yearned for the wealth of the sea, not the land.

Asian women had been banned from the country after the 1901 White Australia legislation, so apart from a few long-term residents there were only the Aboriginal women available to provide company for the indentured men. As always, exploitation occurred, but also relationships developed between Aboriginal and Asian people, of every kind from brief liason to marriage. They were deplored as ‘immoral’ by whites, but they provided the comfort of family life to men a long way from home, and their handsome descendants today make up a large part of Broome’s population.

A lugger like Redbill would usually carry seven seamen, and in the boom days as many as 2,400 indentured Asians were employed in Western Australia every year. Between 1905 and 1915 they crewed on around three hundred to three hundred and sixty Broome luggers and on forty to sixty luggers from the smaller ports, Onslow, Cossack and Port Hedland. In Broome itself there were usually around two thousand Asian people to one thousand Europeans.

Yet for all of its activity the industry was being quietly undermined. In 1905 Japan won a war with Russia and crushed a major market for palace and church mother-of-pearl in the process. Fifty-five luggers had been wrecked in the two cyclones of 1908 and the loss hit the whole town. Some of the pearlers faced bankruptcy, so would quietly rent their boats for a season to Asians and remain as the ‘dummy’ owners.

The Pearling Act stated that aliens – foreigners – were not permitted to own, hold licences, or have a financial interest in pearling vessels, but dummying was widely accepted and occurred for years. In some ways it was little more than a private agreement between master and diver as to how the profits of a lugger trip would be allocated, but it provided a small, reliable income during difficult periods when the alternative was financial ruin, and at one time or another most of the masters had a stint as a ‘verandah pearler’.

* * *

It was ‘the most disastrous cyclone that ever occurred on land or sea in the Nor’-West’, wrote the shaken editor of the Broome Chronicle on 26 November 1910. Broome was believed to be fairly safe from cyclones, but on 19 November the town had been struck by a terrible storm:

About 11 o’clock the more flimsy structures commenced to give way, and the wind increasing in force every few minutes, by 1.30 o’clock it became so serious that people were fleeing in all directions seeking shelter from falling roofs and buildings. Sheets of iron were driven before the wind like sheets of paper . . .By 2 o’clock the storm was at its height, and the destruction of the town commenced with a vengeance. Roofs were lifted and carried hundreds of yards away, buildings fell in or were blown down, trees were uprooted or broken off; telephone poles were either snapped like carrots or were bent like wax matches . . . to-day pretty Broome presents a scene of desolation . . .

Damaged luggers after a cyclone. Miss Withers' boat Whiteboy, dismasted, right foreground. This was taken after the cyclone of 23 January 1926 at Broome.

Forty-nine people died and twenty-three luggers were lost. Telegrams of condolence arrived, among them one from Parkes and Co., Pearlers, Onslow: ‘Kindly convey to sufferers disastrous hurricane our deepest sympathy’.

The Parkes had every reason to feel for Broome, but they were apparently undaunted by their own situation and in 1910 they bought lugger Chaffinch. Fred Parkes wanted to commission another: ‘I prefer boats of the size of Redbill . . .’ he wrote to his brother Bert, who had been living on the schooner Rescue, but was now moving ashore because his wife ‘Sis’ and their children were returning from a visit to Britain.

The year 1911 in Onslow opened well enough. There was little local competition, only C. F. Nystrom with four luggers, and H. Lister Holmes with two; while the Parkes employed over 40 indentured men and held licences for Redbill, Ibis, Chaffinch, Lapwing, Hawk and Rescue. But the region around Onslow was not called ‘cyclone alley’ for nothing: yet another major storm struck on 13 February 1911. It stripped windmills in Onslow, but this time the worst of it fell upon the Montebello Islands, said the Broome Chronicle on 18 February:

. . . the full force of the cyclone had been experienced out there on Monday night and Tuesday morning. These islands are at present being used as the lay-up quarters for the pearling fleets of Messrs Parkes and Co., and Mr C.F. Nystrom.

On Monday morning most of the boats being out working some 15 miles to the Southward, and a very heavy North East swell rolling in with a falling glass, it was decided to run to the islands for shelter.

A light South East breeze was blowing at the time the boats reached the lagoon where the schooner Rescue is securely moored for the hurricane months, with her masts out and everything made snug . . . After 4 p.m. the glass fell very rapidly, and a heavy swell came rolling in through the lagoon, which is practically landlocked. At 7 p.m. it was blowing almost a hurricane from the Southward, rapidly increasing in force and raining in torrents.

At midnight during the height of the blow the luggers Lapwing and Curlew dragged their anchors and were driven onto the rocks, where they were almost smashed to pieces, the crew fortunately being able to scramble ashore unhurt . . .

Curlew (owned by Harding) and Lapwing were completely wrecked. Hawk was driven onto a sandbank, Chaffinch and Thistle (Nystrom) lost their masts, but schooner Rescue remained safe at her mooring. Lucky Redbill and Ibis were ashore in the lay-up, together as usual, and were relatively unscathed:

The Ibis and Redbill, which were both being repaired, each lost a rudder, and had their bulwarks slightly damaged . . . The house on Hermit (sic) Island, occupied by Mr. T. H. Haynes, who is engaged in trying to cultivate pearlshell, was entirely demolished and blown into the sea, the occupants having a very narrow escape.Parkes and Co. were seeking investment for a pearlshell culture business to be based near Port Hedland, and Fred Parkes spoke to Thomas Haynes some months after the cyclone. He reported with a touch of cynicism to another pearler:

[Haynes] says that undoubtedly the bulk of the shells are bastard shells, but that some he grew in his pond he thought were the real thing, only they were too small to determine. And unfortunately they all disappeared, eaten by fish or shrimps, he thought. He evidently is no nearer the solution of successful pearl culture than when he started 9 years ago.Haynes returned to Britain and carried on lengthy negotiations to extend his leases. He finally abandoned the Montebellos project after war broke out in 1914.

Despite the cyclone the Parkes carried on pearling, and in June 1911 bought another boat named for a bird to join their little flock of luggers (‘I have called her the Mopoke,’ wrote Fred to Bert, ‘I had decided on the Dabchick but found there were already three of that name’). Astonishingly without cyclones or other mishap, Redbill, Ibis, Chaffinch, Hawk and Mopoke worked peacefully for the next few years.

Fred wanted the company to sell the schooner Rescue, so Bert went into parnership with two Onslow seamen, Nilsen and Hansen, to buy Rescue as a trading vessel for the North-West Lightering Company. Fred disapproved of his younger brother’s new enterprise, and his previously affectionate letters became cooler:

Very sorry indeed to hear about the Japs. Hansen does not seem to be able to work them . . . More than sorry to hear that we may soon need an overdraft. Was looking forward to another divvy as a Xmas box.The pearling improved and an overdraft was not required – they actually made a profit of £2,540 in 1911 – but the take the following year was disappointing: ‘Am sorry our boats are doing so little for shell’, then, ‘Pleased to hear our boats were on a bit of a patch but sorry to know our divers are no class’.

In 1913 Fred took his 12-year-old son Frank, convalescing from illness, to sail on the luggers for three months around the Montebellos; Frank was much improved by the experience. That year the Parkes hired better divers from Broome, but 1913 ended badly for Bert and the North-West Lightering Co. when Rescue lost her mainmast just before she was due to take on a lucrative shipment of cargo.

Bert Parkes was also chairman of the Ashburton Road Board, the political power of the region. Argument about the future of Onslow had arrived at the dream of building a new, deep-water jetty at Beadon Point on the coast, and relocating the entire town to that site, twenty kilometres away: at the time Onslow had 40 houses and a white population of 145 people. Argument raged, engineers visited, committees convened, but the grand plan finally came unstuck; a severe drought over these years meant that the region was simply too poor to support a major public works project, and until the 1920s Onslow stayed just where it was.

* * *

At the start of the 1900s pearlshell divers were drawn from a broad range of racial groups, but over the next decade the Japanese increasingly dominated – by 1907 half of the Broome divers and tenders were Japanese, and by 1915 over seventy per cent were.

In the late nineteenth century the feudal Japanese had hastily modernised; the world was mad for Empires, and Japan wanted to join the club. Britain and Japan signed an Alliance Pact in 1902, and victories in minor wars with China and Russia brought Japan onto the world stage for the first time: the island state was sometimes called the ‘Great Britain of the East’.

The ultra-nationalists who controlled Japan were descendants of the warrior clans that had ruled the country ruthlessly for eight hundred years. The vast majority of Japanese were poor peasant farmers or fishermen, but once allowed out into the world they quickly became skilled at whatever they took on. The Japanese who came to Broome from the 1890s onwards were usually fishing folk from a beautiful rugged strip of coastland south-east of Tokyo – Wakayama-ken – many of them from the small town of Taiji and nearby villages.

The wisdom of the time muttered that the Japanese were good divers because they had some sort of physiological advantage; this was not necessarily true, but certainly the performance of a group of English divers in 1912 did little to challenge the Japanese reputation. They were brought out to Broome for a season to test the possibility of replacing Asians with Englishmen, to the great enthusiasm of White Australia legislators. It was obvious to the master pearlers that white divers would cost them more and would find life on the old luggers very difficult, but several grudgingly accepted the men for trials. (Captain Gregory was not involved as he was on leave for nine months in Britain at the time.)

The outcome of the experiment was less than promising. Some of the English men had only a few months diving experience and of course, none of them knew anything at all about locating elusive Pinctada maxima. The best of the group, William Webber, died of the bends on a lugger near the Ninety-Mile Beach, and another, John Noury, also got decompression sickness and had to spend months convalescing. There were rumours of sabotage, but it was hardly necessary: the reality of pearling life made this a fairly standard casualty rate even for experienced Asian divers. Most of the surviving white divers left Broome as soon as they possibly could, but two of them remained in the region; both died of the bends in separate incidents a year later.

Perhaps the Japanese advantage was more of a cultural one – they seemed to be the only group in Broome (and that included the master pearlers) who saw value in working together co-operatively. They set up Japanese Clubs to provide each other with legal and social protection. They found cohesion in recruiting from their home villages, and had the incentive of escaping poverty in Japan, to return with relative riches in only a few years. There was a career structure on the luggers with increasing levels of pay and status, from try (trainee) diver to exalted first diver. The job of tender – caring for the airhose and lifeline – was a post for retired men.

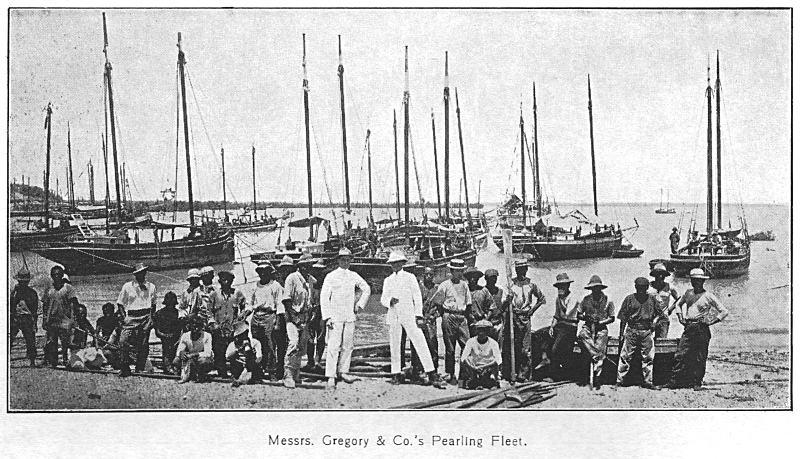

Captain Gregory was one of the few masters who understood how much his prosperity depended on good relations with the Asian community; many of the other pearlers were deeply xenophobic and the clever, industrious ‘Japs’ were the embodiment of their worst fears. It is telling that out of sixty-four photographs of Broome master pearlers, boats, camps and domiciles in Battye’s 1915 History of the North West of Australia, only two images show the seamen who were the foundation of the industry.

One is a standard view of sailors assisting a (white!) diver out of the water and the other is ‘Messrs. Gregory and Co.’s Pearling Fleet’. With luggers bobbing in the background, Captain Gregory and shell-opener William Clarke stand tall in the centre, with about thirty Asian men in relaxed poses around them. The other 34 pages of the Broome section of the book, full of portraits of stern Edwardians who were remarkably keen on Freemasonry and ‘clean, manly sports’, would otherwise imply that those gentlemen did all of the hard work themselves.

Gregory's camp, taken around 1914.

* * *

The Pearling Act 1912 regulated the issue of licences for ships, master pearlers, divers, pearl dealers, and pearl fishers (lugger crews), and one of its requirements was that before issuing a pearl fisher licence the superintendant had to be satisfied that that the fisher was a male. So women could not be pearl fishers, but they could certainly be pearlers. A few women in Broome owned luggers – Rose Gonzales, Anastasia Percy, Amy Chapple – but their formal occupation was ‘married woman’ and their property really belonged to their husbands.

One exception was Miss Elizabeth Withers. She is mentioned in Forty Fathoms Deep with the intriguing comment: ‘And the cruise so far had been profitable. Pleased were the crew and pleased would be Miss Withers, the girl pearler of Broome who owned the Leighton.’

The Register of British Ships states that ‘Lizzie Withers of Broome W.A. (Spinster) Pearler’ bought the Leighton in February 1909. She licenced the lugger for pearling every year until 1920. Miss Withers also owned Pansy, Whiteboy, Onie and Swan, and worked them on and off until the mid-1920s. She was prosperous enough to buy and sell a number of houses over the years.

Although the male pearlers and their wives and daughters attended the town balls, Miss Withers never appears in the newspaper listings of Broome ladies and their beautiful gowns, although she once offered a reward in the paper for a fashionable, expensive belt she had lost – black velvet with a baroque pearl mounted in gold. She must have been a recognised member of the white community, because the Nor’-West Echo reported her departure on the steamer – ‘Miss Withers sailed by the Gorgon on holidays bent’ – along with other leading lights of the town in September 1913.

She appears to have had a younger brother who was also a pearler: the Broome Chronicle of 25 December 1909 lists nineteen new members of the W.A. Pearlers’ Association, including E. Withers and Miss E. Withers, and when Private Ernest Withers was killed in France in June 1917 aged 25, the local Red Cross society offered its condolences to Miss Withers. (Possibly lugger Onie, which first appeared in 1915, commemorated a pet name for young Ernie.)

In 1917, after Ernest died, Lizzie Withers advertised her foreshore camp, luggers and three houses for auction, but she continued pearling so apparently did not sell up at that time. Leighton was driven onto the shore near Bannagarra Creek by a willy-willy in April 1920; the crew survived but the boat was wrecked. Whiteboy and Swan remained registered to her until 1925, then were sold to the ‘Department Controlling the Insane’ and later damaged in a cyclone, the Chief Pearling Inspector reported to the Fisheries Department in 1927: ‘The two boats . . . once worked by Miss L. Withers, were sold as they stood after the storm for £10 the lot. They were in total disrepair.’

Her photograph from around 1910 shows neither a girl nor a ‘spinster’: instead, strong-faced and good-humoured, Lizzie Withers looks as if she would have preferred to be out sailing a lugger herself, were she not so anchored by her coiffeur and corsetry.

Miss Elizabeth Withers, pearler of Broome. Her wise eyes, sardonic smile and capable hands are intriguing, but very little is known about her.

* * *

The year 1912 was to be significant not only for the white divers. After a week of squalls, on 21 March the weather blew up into a hurricane stretching from Port Hedland to Broome. The recently-commissioned coastal steamer Koombana, 340 feet long with watertight doors for every compartment, had left Port Hedland on her regular run to Broome, planning to put far out to sea to weather the storm. She did not arrive, and after days of mounting concern, and weeks of hope that she was simply drifting out of contact, it was finally accepted that the Koombana would never be seen again. More than twenty people from Broome disappeared with the vessel and only a few scattered pieces of wreckage were ever discovered. (Fred Parkes in Perth was appointed one of the three Assessors on the Koombana enquiry.)

The cyclones of 1908, 1910 and now this shocking loss, brought a sombre note to the frontier town. Just three weeks after the disappearance of the Koombana, the liner Titanic was sunk by an iceberg, killing over 2,000 people: the treachery of the sea seemed without limit. The Balkan Wars stopped for a while then started again. Captain Scott’s expedition to the South Pole ended in disaster, the men dying in a blizzard-bound tent only miles from a food depot. The world was suddenly more uncertain that it had ever seemed before.

Yet the pearling season went well – a number of valuable pearls were discovered and shell was selling for an average of over £250 a ton for the first time. Luggers with engine air-compressors were starting to appear, and because their divers could go deeper their annual take was reaching 10 tons, twice as much as before. Captain Gregory returned to Broome in October 1912 and was elected to the committee of the Turf Club. A road to Cable Beach (‘a real beauty spot’) was proposed – Fred Everett and Mr Murakami offered £25 each for a construction fund.

The mile-long Broome jetty, with its little steam tram for passengers and freight, was in a state of disrepair. In July 1913 the tram engine, pushing carriages from the rear towards the town, left the track, tore its buffers off and sent the passengers careering out of control along the jetty. The ticket collector managed to apply the brake in time, but State government neglect of the essential facility remained a sore point.

Another sore point was the municipal council, engaged in endless internal battles, unable to cope with the squalid sewerless foreshore, the roaming goats, the potholed roads and some suspicious irregularities in the voting roll. A ratepayers’ meeting in November 1913 carried the resolution that the entire council should resign and elections be held; Captain Gregory became one of the new councillors.

Far away from Broome’s little quarrels, the nineteenth-century European empires were jostling, squabbling and flexing their muscles in alliances with new friends and old foes; and arming, arming, arming. Like a tropical cyclone, the trigger would be insignificant, but the environment was primed for a cataclysm.

The 1914 pearling season began. The Panama Canal was opened. Dick Gregory went to Britain in April for a holiday. A decompression chamber was donated to the hospital from diving-suit makers Heinke. Home Rule for Ireland was much discussed. A cockeye on the Ninety-Mile sank two luggers and killed two men. There was more trouble in the Balkans. The Broome Turf Club organised a meeting for September. Several fine pearls were found, one by ‘a local lady pearler’ – Miss Withers perhaps? Some minor Austrian royals were shot in Serbia.

Much shell was raised and record prices were predicted. America and Mexico were close to war. The deadline for replacing Asian divers with white men was pushed back to 1918, to general relief. Austria invaded Serbia. The children’s Fancy Dress Ball was held. Russia mobilised. Another inquiry into the Broome jetty began. Germany declared war on Russia. ‘All symptoms of a coming catastrophe prevail’, said Reuters in Berlin. Tenders were called for 31 chains of road making. Germany invaded Belgium and France; Great Britain declared war on Germany; Japan allied itself with Britain; the Commonwealth declared war on Germany. The United States issued a formal statement of neutrality.

In August 1914, in a flurry of treaties, mobilisations, and pompous declarations, the Great War engulfed Europe like lava. Everyone thought that it would be all over by Christmas.

* * *

The European mother-of-pearl markets collapsed. Factories closed in Paris, Vienna and Picardy. At the outbreak of war, pearlshell was reaching £220 a ton, but the contracts had clauses voiding them in the event of European conflict. Just after war was declared, luggers brought in £70,000 worth of pearlshell which no longer had buyers, and some masters could not afford to pay their divers or crew. By Christmas 1914, when they should have been steaming homewards from Broome, many crewmen were still waiting for their wages. Fear and uncertainty came close to setting off serious riots, but the worst was averted and by the end of January most of the indentured men had managed to return home, apart from forty-two of them who, with great enterprise, were selling their masters’ boats to recover their wages.

In Onslow most of the seamen of the Parkes and Co. luggers had also returned to their homelands between September and December 1914. The company employed only two indentured men over wartime, probably to maintain the luggers, because Redbill, Ibis, Mopoke, Hawk and Chaffinch were laid up. Unlike many who believed that the hostilities would soon end, Fred Parkes wrote in May 1915 to another pearler:

I have no idea of starting again till the war is over and that will not be this year I am afraid. Our boats are better lying anchored in Onslow Creek than losing money by working.Later that year one of the men in the Rescue partnership withdrew, leaving Bert Parkes in difficulties. Fred wrote with with a touch of smugness: ‘I am sorry to hear that Nilson has gone back on Hansen and yourself . . I would not buy the share as I should not care to be in partnership with either Nilsen or Hansen.’

The brothers began to disagree about Bert’s apparently casual style of record-keeping: ‘You have absolutely ignored all my requests to keep [a stock book]’, wrote Fred, and a month later: ‘Only this, if I cannot have an equal say in the management of the business as yourself then I would prefer to be out of it.’ Bert seems to have wanted to continue pearling, but Fred insisted that he sell their aging diving gear, claiming that there was too little profit in working boats (like Redbill and Ibis) that did not have air compressors. The partnership began to fall apart, and Fred wrote to Bert in March 1916:

I am sorry that you are not in a position to buy my share. However . . . I only wish to let you know that I want to get out [of pearling] at the first favourable opportunity.* * *

Dick Gregory had married Alice Griffith shortly before war broke out. He rejoined his Cavalry regiment and went on to command a company in the Camel Corps in Palestine. Captain Gregory resigned his posts as Harbour Master and Inspector of Shipping in order to support Gregory and Co., suddenly strugging in an unimaginably altered world.

The pearling industry was refused the kind of State govenment subsidy offered, when war broke out, to farming and mining: it was seen locally as payback by a White Australia-obsessed government towards a town that had quietly preferred to keep on working with Asian people. Eventually in 1915 some grudging official support appeared and the price of pearlshell recovered briefly when America move into the markets abandoned by the Europeans, but the industry again took a hit when America entered the war. Nearly 120 luggers, one-third of total, were laid up. Some were sold to the remaining masters, others were left to rot.

The Gregory fleet now comprised schooner Hercules (part-owned with O.W. Blackman) and six luggers. Three recent additions were Charlie (renamed Langdon), Ida and Esther (Fanny had been sold in 1913). Over the four years of war Gregory bought five more boats – Rose Petal, South New Moon, Meave, Heather Flower and The Gerald. The Nor’-West Echo told of a cockeye at Broome in January 1916 which caused over £1,000 worth of damage to Gregory’s uninsured boats: he shrugged off commiserations and said, ‘It’s all in the game’. Lugger Esther was lost in 1918 and so was the fleet schooner Hercules, blown ashore in March near Barred Creek.

Yasukichi Murakami and the other town traders were badly affected by the war: the younger pearlers, always happy for a gamble and a new horizon, rushed to enlist, while the departure of so many seamen impacted services and suppliers all over town. Most businesses survived only on credit or loans. Beyond his financial woes it was a hard time for Murakami: his younger brother Ryozo came from Japan to work on Fred Everett’s lugger, but he drank heavily, became ill and died in April 1917.

Like everyone else, the editor of the Nor’-West Echo proclaimed with jingoistic fervour the courage of the ‘Broome Boys’. When the first casualties occurred the paper printed large black-bordered obituaries and letters of thanks from the grieving parents. As time went by and the inconceivable scale of the tragedy unfolded, the obituaries became briefer and the parents no longer had the heart for letter-writing. There were roughly nine hundred whites in Broome before the war, male and female, old and young, and almost every eligible man enlisted. Of two hundred and thirty-two soldiers, fifty-seven never returned; a loss of one in four and a staggering setback to the small town.

Towards the end of the war the death notices had become just a few lines. On 8 December 1917 the paper noted: ‘As we go to press we learn of the death, from wounds, of Captain ‘Dick’ Gregory’. That was all. Just one among the many whose lives were so carelessly discarded, he had been killed in Gaza at the age of thirty-six. It was an odd coincidence that the younger brothers of both Murakami and Gregory had died within months of each other, and a sense of loss may have strengthened their bond.

Major Fleming Gregory’s name appears on the war memorial in Bedford Park, along with that of Private Ernest Withers and fifty-five other young men who loved a gamble and a new horizon. We can only imagine the effect of the death of his brother on Captain Gregory, so far from his Welsh homeland, but it was probably as heartbreaking as it was for so many others.

* * *

Bert Parkes’ schooner Rescue was totally wrecked in mid-1917. His brother Fred could not refrain from rubbing salt in the wound: ‘I was very sorry indeed to get the news about the loss of the Rescue. Had it happened before she was repaired it would not have been so bad.’

The feeling between them was so unfriendly by 1919 that Fred wrote to another brother about a family wedding :

Unfortunately there was a rift . . . Sis [Bert’s wife] was receiving . . . and when Alice & I went in she deliberately turned her head away & did not receive. Neither of us are ever likely to forgive the insult.The partnership ended that year. Redbill and Ibis were the oldest of their vessels and Bert put them up for sale. In June 1919 a cheque of £200 for each boat was received from a canny buyer – luggers were selling for £350 at the time – and on 10 September 1919 a note appeared in the Register of British Ships for the Port of Fremantle, recording the transfer of luggers Redbill and Ibis from the ownership of F.L. Parkes and Co. of Onslow to that of Captain Ancell C. Gregory of Broome.

At the same time Bert bought Chaffinch, Mopoke and Hawk with skipper Axel Hansen for H.M. Parkes and Co. – his own pearling business at last, but not for long: Hansen died in the wreck of the schooner Sea Flower at Cape Leschenault in September 1923. Bert closed down the company and advertised Chaffinch and Hawk for sale, but the market for old boats was over, so they were taken out to the camp at Lugger Cove in the Montebellos and left moored.

Their remains, sunk by yet another cyclone, gave rise to a local tale of a lugger that had been half-built by one of the Parkes before he marched away to die in the Great War, but it was nothing so romantic. A nephew in Britain had been killed, but the Parkes were too old and their sons too young to fight; it was no more than a family feud that had closed down the company that named its boats for birds, and sent straight-stemmed Redbill out to raise the giant iridescent shell of the Montebellos.

2. The Phantom Fleet

Gregory was Broome’s brightest citizen but had been born 3 centuries too late. He had all the instincts of an Elizabethan adventurer . . .

- A.A. Milne-Robertson

When the war to end all wars shuddered to a halt on 11 November 1918, there would still be no relief. Even as the Armistice was signed the first ominous symptoms of ‘Spanish Influenza’ appeared, and joy at the war’s end faltered as the disease spread. For almost a year the newspapers reported deaths in Sydney and Melbourne: sometimes only a few people, sometimes up to fifty, every single day in both cities. After six months it was widespread in Perth, but seemed less virulent. After nine months it hit Broome and two-thirds of the town became ill, but the virus had weakened and only a few people died. It was not until late 1919 that life could begin to return to normal.

Only two hundred boats were pearling at the end of the war, but the industry began to recover and a boom took shell prices back up to £240 a ton. Good times had apparently returned, and Redbill and Ibis were to be there in the thick of it. Their new home was Gregory’s foreshore camp near the Customs House (now the Broome Historical Museum), which, Tom Ronan recalled,

. . . with it’s founder’s flair for getting the best of everything, held a larger expanse of foreshore than most of its rivals . . . from the head of the stairway outside our living quarters we controlled a view of Roebuck Bay from Red Point, its nor’easterly limit, to the sandhills on its southern bank, with their blueness in the midday haze . . . the flat mirage of mud and water in the foreground . . . Our shore living quarters was the upper floor of a building made, as were all foreshore camps, from discarded parts of old ships. There was an Oregon pine mast in each corner of the square, and one in the middle to hold up the roof . . . in a high wind it swayed in an almost eerie manner.Work in the lay-up season would start at six in the morning, with Captain Gregory there before breakfast:

White-trousered, silk-singleted, white-helmeted, one of his personally imported Egyptian cigarettes forever in his mouth, he watched that work being done . . . His great strength was that, not only could he criticise most obscenely a job that was not being well done, but he could take it over and give a practical demonstration. . . . There was no waste, but there was no skimping: the Skipper was too proud of his fleet not to ensure that every ship in it was well found.World War I had brought an end to the reign of the giant square-rigged ships of the British merchant fleet, which demanded of their crews such endurance and self-discipline. As a boy of sixteen Gregory had signed with Goldberg and Sons of Swansea as an apprentice, and sailed for four years on the four-masted barque Vanduara. In 1900 he became Second Officer on another four-masted barque, Andorinha, and sailed to Cape Town, then Newcastle NSW, South America, and back to Newcastle. There he signed as First Officer on three-masted full-rigged ship Rhuddlan Castle and voyaged to Chile, then Antwerp via terrifying Cape Horn. His last windjammer was a new three-masted steel ship Brynymor, then in 1904 he ‘moved into steam’ with Alfred Holt and Co.’s SS Sultan and SS Charon, until he settled in Broome in 1906. There his sailing vessels were on a smaller scale altogether, yet even they required as much care and maintenance as any great wind ship.

During the lay-up a lugger like Redbill would be stripped of all ropes and sails and spars. Her false floors would be lifted and ballast removed and cleaned, bilges emptied of the ‘stinking refuse’ of ten months at sea; and sea-cocks opened for a week, so that while she sat on the mud the tide entered her and, for a time, dislodged the cockroaches. With gleaming red copper the crew would renew the plates that protected her hull from borers. The tops of her masts would be painted with coloured bands to identify her at sea, and surfaces covered with cheerful hues that we might never imagine from old grey photographs:

The wood of trodden decks and cabin-tops disappeared between coats of paint as gay as Chinese lanterns, canary-yellow and orange-red and peacock-blue . . .

Redbill was sixteen years old but must have been maintained well enough, because in the 1920 season she worked out of Broome for the first time with her new pearling licence, B11, bright on her bow; Ibis was B12. Gregory’s fleet now carried numbers B1 to B15, a mark of his influence. He was president of the West Australian Pearlers’ Association for over four years from 1917, and had also been elected Mayor of Broome in November 1918, but the council was replaced by a Road Board soon after and he returned to being simply one of its quarrelsome members.

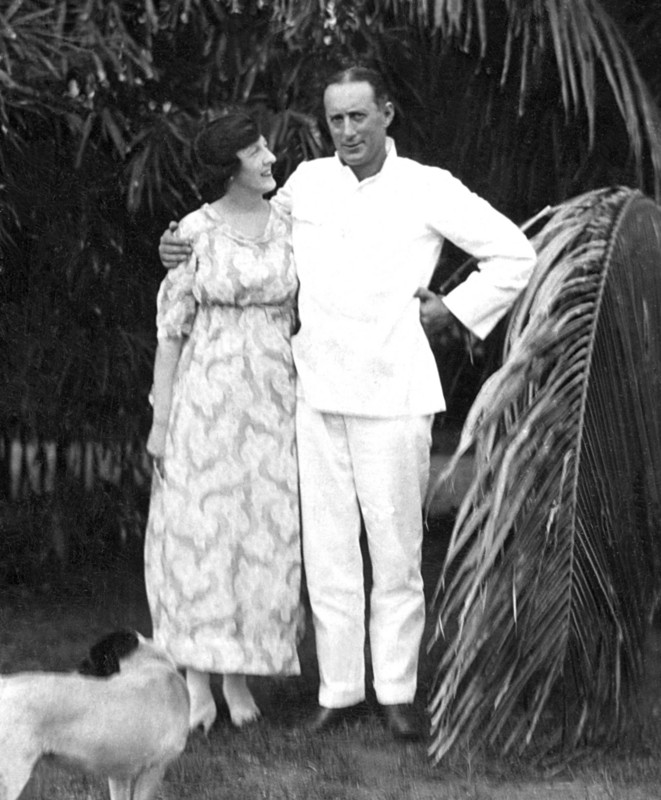

Gregory had married Kate Villiers of Melbourne in April 1915, an attractive woman with a lovely singing voice and great strength of character. For someone raised in the city, life was hard on the pearling coast; servants helped, but the extremes of the climate were a constant pressure. Gregory would bring Kate small gifts every day like embroidery silks; they would dress formally for dinner in the evening, and after parties go driving to Cable Beach and back in the humid night air.

Their house was in a style that became common to those of the master pearlers. It was built in 1915 by a Japanese carpenter, Gurachi Hori, who carefully jointed all of the wood together instead of using nails. The frames and fitted floors were made of jarrah, with white-painted corrugated-iron cladding on the walls and roof. French windows opened onto wide latticed verandahs which could be enclosed with shutters during storms. It had three bedrooms and an office extension to one side, and was on the corner of Robinson and Anne Streets, on the same block as the Continental Hotel.

The post-war period was also good for Murakami at last: his life had taken some extraordinary turns. He had first come to Broome in 1901 as the apprentice of trader Nishioka and wife Eki, a photographer. Nishioka had died and Murakami and Eki carried on the business under the trade name ‘Nishioka’, but it began to run into financial trouble just before the war and the shop had to close in 1915. Eki secretly took as much money from the business as she could find and returned to Japan, leaving Yasukichi to face bankruptcy in 1918.

Gregory had bought the Dampier Hotel, previously the Pearler’s Rest, in 1916, with Murakami as manager and silent partner. He was not only highly efficient, but his presence brought other Japanese to the Dampier, and Gregory was able to have the pick of the crews. It was, of course, completely illegal for an alien to have an interest in any hotel, but this clearly did not bother either of the partners.

When the bankruptcy proceedings occurred, both men swore that Murakami was owed only a half-share of the hotel’s profits, not a half-share of the ownership. Hugh Richardson, who openly disliked Gregory and Murakami, said that they were lying, but the court did not agree and the Dampier stayed out of the distribution of Murakami’s assets to his creditors. His bankruptcy was finally discharged in 1921.

In about 1913 Yasukichi had met a beautiful young Australian woman of Japanese descent, Shigeno Theresa Murata, from a Catholic family of Cossack. Theresa spent some years in Japan with Yasukichi’s family, then returned to Broome in 1919; the Murakamis eventually had nine children, including a set of twins.

Children were also on Gregory’s mind. In 1921 Kate gave birth to a daughter, their only child Pamela. She was christened Audrey Pamela Villiers Langdon Clement Gregory, and of the boats that Gregory built over the next decade, one was called Pam and another Bunty after one of Pam’s dolls. At 43, fatherhood had come late in his life, but it clearly meant a great deal to him.

* * *

A strange quest preoccupied Gregory, too. For all of his buccaneering ways he was a child of the Victorian era, ‘as loyal a son of Empire as ever was’, said the writer Mary Durack, who knew him well. He served as sub-lieutenant in the British Royal Naval Reserve, and in 1912 had written to the Department of the Navy, offering to set up a branch of the Royal Australian Naval Reserve in Broome. The Navy was enthusiastic until enquiries in London brought the response that there was no record of his service with the Royal Naval Reserve; the same letter explained that men who had gone to the colonies were struck off the register, but the Navy drew back, war intervened and the matter was dropped.

This left a shadow of doubt on Gregory’s past which lived on in gossip and was used against him by political rivals. Yet H.V. Howe, who was later Military Secretary to the Minister for the Army, wrote to Mary Durack that ‘Gregory was definitely an officer of the Royal Naval Reserve’. She replied:

I do remember . . . Greg one day taking particular trouble to show me his name and standing in some Navy gazette. He must have suspected that I had been told – which was indeed the case – that he had never had any association with the Royal Navy at all.After the war Gregory tried again. When in Melbourne in March 1920, he took the bold step of calling upon the First Naval Member, who was much impressed, and immediately took to the idea of setting up a network of Navy agents in remote ports, noting to the Minister: ‘I would propose with your approval to appoint Captain Gregory as an Honorary Lieutenant R.N.R. It would be invaluable to us to have a reliable officer acquainted with sea to send us periodical information from Broome and the N.W. Coast.’

The Minister approved, but when Gregory reported for orders they were not, as he had hoped, to run a branch of the Reserve; instead he was given an Australian Merchant Ship Cypher Code Book and told to provide intelligence reports on unauthorised shipping, suspicious characters, coal deposits, unsurveyed ports – and the ‘alien populations of Broome’. He was suddenly in something of a bind: he wished to honour his commission, but the cost of it might be to provide ammunition to those who were clamouring for a White Broome, so he had to choose his words carefully. His first report showed a clear grasp of Japanese political factors, discussed the Asian communities in the industry, and listed the numbers and professions of local Japanese to a level of detail that suggests that Murakami helped him compile it.

He also wrote, ‘There is not . . . any unrest or disputes at present . . . amongst the various races of aliens themselves,’ which was premature, because only eight months later, on December 20 and 21 1920, the famous Japanese-Koepanger riots took place. Gregory and Murakami were prominent in helping to calm that situation down. In the official reports from Gregory, Pearling Inspector Stuart, Sub-Inspector Special Police Gull and Police Captain Bardwell, it is Gregory’s writing that stands out for its vivid sense of the human element of the riots. The other three reports barely mention the six Asian men who were violently killed, but focus instead upon minor injuries received accidently by four white men.